Is Refined Food Really Organic?

By Brane Žilavec, May 2012

Here are presented examples of three quite common practices of labelling Organic Refined Foods (see Glossary of the Key Words). In several products you might notice that two, or even all three methods are used, but we will focus in each example on one practice only.

6.1 Incorrect Labelling of Organic Sugars

We will start with the practice of incorrect labelling of partially, even highly refined sugar as 'Natural' or 'Unrefined' or 'Raw'.

Organic Natural Granulated Unrefined Cane

Sugar

The natural alternative to white refined sugar

Colour of sugar:

Whitish

Amount of sucrose: 99.3%

Raw Cane Sugar – Unrefined granulated sugar

Colour of sugar: Whitish

Amount of sucrose: No information

Raw Cane Sugar

Colour of sugar: Whitish

Amount of sucrose: No information

Now, the problem is evident. My eyes are seeing three whitish, crystalline, highly refined types of sugar. My visual perception is confirmed by the taste and the smell. The taste of these three sugars is very similar to the taste of white sugar and very different from that of any type of whole or brown sugar I have tried so far. The same is found with the smell: while whole and brown sugar has a rich smell, resembling that of molasses, the above sugars have a very similar smell to white sugar.

Such very loose use of words 'Raw – Unrefined – Natural' does not provide customers with clear information about what they really get in the product. Of course, I am here referring to the cases when ‘Raw Cane Sugar’ is used in products where it is not possible to see what type of sugar is inside. I am sure that many organic customers would be unpleasantly surprised if they knew what ‘Raw Cane Sugar’ really means.

There is another thing: as a rule organic sugars do not contain nutritional information on the package which enables customers to see how much sucrose the product contains; while the mainstream sugar companies do have such information on their sugars.

It is evident that there exists a need for the clear labelling of organic sugars. This would prevent many customers from consuming refined types of sugar unintentionally. As is the situation now the words 'Raw – Unrefined – Natural' are an example of euphemism [1]. These words are used just to make sugars look better, healthier and more nutritious than they really are (for more examples see Appendix 7: Inquiry about Organic Sugars).

6.2 Hiding Refined Ingredients

The second practice used among organic producers is hiding Organic Refined Foods under general names in the list of ingredients. This is the most common and widespread practice used among organic producers, which does not allow the customer to make informed choices of food products and to choose whether they want to consume Refined Foods or not.

Example 1: Green & Black's Butterscotch chocolate

Among the ingredients are listed Organic Raw Cane Sugar and Organic Cane Sugar. After an inquiry the following nutritional information for Organic Raw Cane Sugar was given by the producer (average values per 100g):

In quite a lengthy reply no information was given about the Organic Cane Sugar. But one can assume that it is even more refined which means that it contains somewhere between 99.5 to 100% sucrose. The result is: in spite of the fact that both sugars are highly refined types, the consumer cannot know this or he might even fancy that raw cane sugar is unrefined, brown sugar.

Example 2: Island Bakery Organic Shortbread

Ingredients: Wheat Flour*, Butter (32%)*, Sugar*, Sea salt. (* organic)

If we now look at the shortbread itself we can see a typical example of a cookie made from highly refined ingredients – very probably white flour and highly refined sugar. Why did they not write then: White Wheat Flour, Butter, Refined Sugar (with the extraction rate)? Is this really so hard to do? Or maybe it would not look so ‘wholesome’, ‘palatable’ and ‘sublimely’ (words from the text on the package) as it looks in the above list of ingredients?

Example 3: Yeo Valley Yogurt ‘Inner Balance’

On the list of ingredients are among others Organic Sugar and Organic Invert Sugar Syrup. After an inquiry the following information was given by the producer: "We use Organic Cane Sugar that has been partially refined and is light brown in colour. There is approximately 5% of added sugar." The only question is now how much is ‘partially refined’? But it is clear that invert sugar syrup is even more processed than white sugar (i.e., sucrose), for the process of inversion means splitting of sucrose into its two component sugars – into glucose and sucrose. I just wonder how this might affect the inner balance of a person consuming such yogurt on a regular basis.

Example 4: Rock's Organic Elderflower Cordial

List of ingredients on the bottle: Organic Cane Sugar, Organic Elderflower Extract (34%), etc. After an inquiry the following additional information was given by the producer:

Because the sugar is listed first it means that the amount of refined sugar must be somewhere between 35 to 50%. I am really interested in how many customers who drink these cordials are aware that up to half of this produce is made from the highly refined type of organic sugar, hidden in the liquid? Are not sugary drinks among the main culprits for the escalation of obesity rates?

6.3 Giving False Impressions

Here we are looking at the most sophisticated practice that uses various elements (logos, nice words, descriptions of positive aspects, and attractive images) which in themselves are correct, but nevertheless give a false impression that the product is more whole and natural than it is in reality.

Example 1: Swiss Organic Oat Pillows

On the back side one can read the following product information: "Muesli - the typical and traditional Swiss meal for breakfast, a light lunch, snack or even evening meal with added fruit, yoghurt and milk went around the world and became world famous. Still today we develop the thoughts and ideas of the famous Swiss Doctor Bircher-Benner, the inventor of Bircher-muesli in the 19th century... These organic oat pillows bring tradition and modern lifestyle to its peak – the wholesome, natural oat flakes are shaped into crispy pillows for your enjoyment. Try the tasty Swiss organic oat pillows with fruit juice, milk or yoghurt and add fresh fruit to your liking – or nibble them as a healthy snack! Natural energy from organic oats!"

On the list of organic ingredients are: Toasted oat flour (46%), flour (wheat, rye), oat flakes (12%), sugar, barley malt. After an inquiry the following information was given by the producer:

I wonder what would be the comment of Dr. Bircher-Benner about this product and its advertising?

Example 2: Amisa Spelt Ginger Cookies

On the package is among other things written: "A nutritious grain: Spelt is an ancient grain type rediscovered and appreciated now for its nutritional values… Unlike modern wheat, which has been intensively cross-bread to increase yields, spelt has retained many of its original traits and remains nutritious and full of flavour." Among the ingredients listed are Demeter Spelt Flour and Demeter Raw Cane Sugar.

Because the company uses the ‘Whole Grain’ logo on their products whenever they use wholemeal flour, it is clear that the above spelt flour is not whole. From the cookies themselves it is not so evident what type of flour is used; it might be brown or white, or something in between (and for sugar we have seen what Raw Cane Sugar can mean). The above claims are true for the whole grain and the products made from whole spelt flour. So why did the producer not use the whole spelt flour then? Is this the way "to be a little different" and to "create food to suit individuals"?

Example 3: Duchy Originals Highland All Butter Shortbread

On the package is written: "Faithful to a century-old family recipe, our all butter golden rounds are slow baked in the heart of the Scottish Highlands using only a handful of naturally delicious organic ingredients such as pure creamery butter, raw Demerara sugar and stone ground flour made from Maris Widgeon wheat grown on the Duchy Home Farm for a rich, smooth shortbread with a crisp, crumbly texture."

Notice how many details are given about the wheat, but not any information about the type of flour. In the frame below is Duchy Originals’ Good Food Charter with the seal Pioneering Good Food. In the charter we can read: "We are committed to making sure that every one of our products is good, does good and tastes good, so that everything we grow and make lives up to the standards you expect from us."

In the list of ingredients is (organic) wheat flour. After an inquiry the following additional information was given by the producer: "The flour used in this product is organic white biscuit flour at a level of 50-60%." So according to this company white flour and refined sugar are ‘naturally delicious organic ingredients’ and shortbread made from them not only tastes good, but also ‘does good’ to consumers’ wellbeing.

I doubt the original highland shortbread was really made with refined ingredients. The fact that it is made from a 100 years old recipe is the very proof of this, for "by the end of the eighteenth century nearly all the population in Britain were eating white flour" [2]. Britain was also the first country where availability of refined sugar improved due to the sugar production in their colonies in India (and later in the Western colonies) to such a degree that white sugar became available also to the lower classes of society. This means that for a true Scottish traditional recipe one should go further back in time before the introduction of refined carbohydrates into modern diet.

Beside this there is no way to survive the harsh natural conditions of the Scottish Highland with such cookies. Just try them – the main effect of each biscuit is just to make you wish for another one. And it does not make one feel really nourished both in body and soul. Is this an example of Pioneering Good Food?

Example 4: Whole Earth Red Fruit Crunch

The first thing which is very striking is the logo WHOLE EARTH. Bellow in white letters is written: "Delicious Clusters of Organic Oats with Redcurrants, Strawberries and Raspberries, the perfect cereal for fruit lovers. With 3% red fruits this scrumptious cereal is an indulgent and yummy way to start your day!"

On the back side is written: "The Whole Earth Story began in 1967 when Craig Sams and his brother Gregory opened Seed, a pioneering, vegetarian, organic and macrobiotic restaurant in Paddington, London, (etc)."

But on the list of ingredients we can find second Sugar (after 59% Oat Flakes), without information about the type and the amount of sugar. After an inquiry the following additional information was given by the producer: "Whole Earth Red Fruit Crunch: The 15.5% sugar used is 100% refined white sugar with no molasses, which is derived from sugar beets and partly from sugar cane."

Now I would like to ask the people who are running the company if WHOLE and ‘macrobiotic’ [see Appendix 2: Macrobiotics Stand to Wholefood vs Refined] are compatible with white sugar? Is this their way to get ‘the perfect cereal for fruit lovers’?

Example 5: Semi 'Wholewheat' Pasta

Here we have the product labelled as 90% Whole Wheat Spaghetti. Clearspring offers Semi Wholewheat Spaghetti and Semi Whole Spelt Penne. At first glance it looks correct and a fair description of the products. But in all cases the customer gets a false impression in regard to the wholeness of the pasta. The graph in 4.1 Wholemeal versus Refined Flour shows that at 90% extraction rate we lose about 65% of fibres. There is a very distinct difference between statements ‘90% Whole Wheat Spaghetti’ or ‘Spaghetti with 65% less fibre’.

Beside this the combination of the words 90% Whole Wheat and Semi Whole Wheat is a contradiction in itself; it can be either ‘Whole Wheat (Wholemeal)’ spaghetti or ‘90% Brown’ (‘Semi Brown’) spaghetti. [3] The way the producer is putting it is the same as saying semi whole circle. A circle must be whole or it is not a circle any more! So it should also be when naming whole grains. Otherwise words are being degraded and in due time will lose their proper meaning.

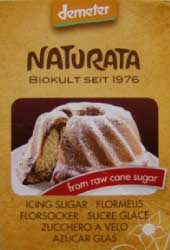

Example 6: Naturata Icing Sugar

This icing sugar is declared to be made ‘from raw cane sugar’. We have seen in the first group of examples that this is not correct labelling of sugar. But there is another reason why this product is placed in this group. On the package is given the following short description of its method of production: "In a special sugar mill in Germany the raw cane sugar is being finely ground. In this way it gets a light colour." [4]

Now it is true that the colour of ground sugar gets lighter than the colour of crystals. But they do not tell to the customer that the colour of ‘raw’ cane sugar which has been ground was already whitish. So a combination of labelling sugar as ‘raw’ and the above description gives a false impression that the white colour of icing sugar made from raw (i.e., brown) sugar is normal. As you can see on the picture below, it is not.

Left: Rapadura, an example of real raw cane sugar (for

colour comparison)

Middle: Demeter Raw Cane Sugar (see Raw Cane Sugar from 7.1)

Right: Naturata icing sugar

CONCLUSION

The guiding principle of labelling any organic produce should be to provide consumers with clear and correct information about the product and its ingredients, as is explained in the brochure From farm to fork – Safe food for Europe's consumers (italics mine): "People want, and have a right, to know what they are eating. Food labelling rules recognise that right. The fundamental principle of EU food labelling rules is that consumers should be given all essential information on the composition of the product, the manufacture, methods of storage and preparation. Producers and manufacturers are free to provide additional information if they wish, but this must be accurate, not mislead the consumer and not claim that any foodstuff can prevent, treat or cure illness." [5]

IFOAM standards recommend that "product labels should identify all ingredients, processing methods, and all additives and processing aids" [6] (italics mine). The Soil Association also encourages their licensees "to provide information on the label which will allow customers to make informed choices about which product to buy." [7] And in the Demeter standards we can find the following statement (italics mine): "An honest product is one whose composition and life history is transparent for all traders and consumers to see. A clear declaration is the first step." [8]

From the above presented examples it is evident that the practices of labelling Organic Refined Foods are not in accordance with these guidelines. The question is: Do we want to tolerate such methods or do we want to give customers what is their lawful right – clear information about what they buy? In my opinion the top priority is to take seriously the law and stop the above presented practices of misleading consumers as soon as possible. Another option is to wait for a more unpleasant stimulus to sort out this unhealthy practice, such as a court case against an organic company for not complying with the laws regulating consumers’ rights. Can you imagine the harm to the whole organic movement if this was to happen?

NOTES