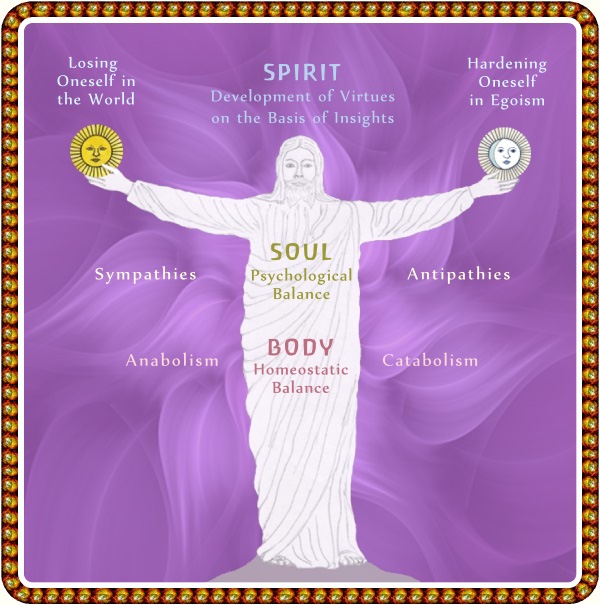

Health as a Balance of Polarities of the Human Existence

The human being is, in his inner constitution, a meeting point of a

great number of polar forces, activities, tendencies and strivings.

Health is a dynamic state of harmonious equilibrium, which can vary

inside particular limits. We need to know that we can frequently cross

these healthy limits without becoming ill because we have inside us the

ability of continual restoration of a healthy balance. Inside us exists

a power which is endlessly striving towards harmony. This ability can

sometimes demonstrate surprising strength – for example, in the cases of

so-called 'spontaneous healing'. Usually we become ill when we develop a

specific habit which causes us to overstep the same healthy limit again

and again, while along with this the ability to restore the healthy

balance is weakened.

If we look for the reasons behind an

unhealthy habit or weakness in maintenance of healthy balance, we come

to the level of soul and spirit. Then we can understand that health is

not just the healthy state of the physical organism, but also the

healthy state of soul and spirit. Every illness is due to a combination

of imbalances on these three levels. There is never just one reason for

an illness to emerge!

Homeostasis: Regulating on a Physical Level

Medical science describes balancing on the physical level as

homeostasis.

It is the dynamic, ever-changing state of the internal

environment of the human body (e.g.

body temperature, blood sugar, blood

pressure, acidity or alkalinity of body fluids, etc.) which has to be

maintained within narrow limits. Homeostasis is maintained partly by the

autonomic nervous system

and partly by the endocrine glands through the

regulation of metabolic processes. [1]

If we observe the human being on the physical level we see "how he

stands before us in his entirety within a polarity. Wherever, in every single organ there is an

upbuilding process there must also be a breaking-down process. If we

look at any one of the organs, be it the liver, lungs, or heart, we see

that it is in a constant stream which consists of building up and

breaking down.

This balance can be disturbed. It can be disturbed to such an extent

that some organ or other may have its correct degree of

anabolism in

relation to too slight a degree of

catabolism, and then its growth

becomes rampant. Or contrariwise, some organ may have a normal process

of catabolism against too slight an anabolism, in which case the organ

becomes disturbed, or atrophies, and thus we come from the physiological

sphere into the pathological. Only when we can discern what a balanced

condition signifies, can we also discern how it may be disturbed by an

excess of either anabolic or catabolic forces. So in every normal human

being there exists a state of balance between anabolism (integration,

upbuilding) and catabolism (disintegration, breaking-down), and in this

balance he develops the right capacity for the soul and spirit." [2]

Our life on earth depends on the proper balance between these two

antagonistic sets of metabolic processes. When

homeostatic balance

is for whatever outer or inner reason outside healthy borders, it will

cause the bodily weakness or an emergence of physical illness –

depending on the intensity and time-span of disturbance.

Soul Composure: Balancing on a Psychological Level

In our daily life we are constantly encountering things, beings and

events which stir inside us feelings of sympathy or antipathy – we either

like something or dislike it. These feelings can be moderate or stronger,

and sometimes can go to extremes and throw us out of healthy balance. But for the sake of our wellbeing "we must achieve a certain balance in life

or serenity. We should strive to maintain a mood of inner harmony whether

joy or sorrow comes to meet us. We should lose the habit of swinging between

being 'up one minute and down the next'. Instead we should be as prepared to

deal with misfortune and danger as with joy and good fortune." [3]

The majority of people would probably agree that too much suffering

and misfortune leads towards extreme feelings of sadness that can end in

the pathological state of depression. However, this is not so evident in

the case of happiness and fortune. How can it be that too much joy can

be dangerous to our health? This can be clearly seen in the case of

psychological disorders. For example, besides people who are suffering

with pathological states of depression, there are also those who are

suffering because of various sorts of mania (i.e. the state of an

extremely intensive mood of joy). In such cases "in psychiatry one

speaks of excited and productive disorders – extravagances of fancy, of

impulse of mania. Enhancement (of feeling well) not only allows the

possibilities of a healthy fullness and exuberance, but of a rather

ominous extravagance and aberration – the sort of 'too-muchness' or

feeling 'dangerously well' – as patients, over-excited, are tending to

disintegration and uncontrol" [4] of their own

personality. There are even people who oscillate between states of

depression and mania. Here we see two polar moods, sadness and happiness

in their extreme, pathological states, and consequently the great

significance of the need for proper control of our feeling moods.

The ability of suitable control of our life of feelings is

especially important if we are on the path of self-development. In such

a case we need to persist in our striving "to hold oneself at a distance

from moods which continually vacillate between being 'over the moon' and 'down

in the dumps'. Man is (in such a case) driven to and fro among all

kinds of moods. Pleasure makes him glad; pain depresses him. This has its

justification. But he who seeks the path to higher knowledge must be

able to mitigate joy and also grief. He must become stable. He must with

moderation surrender to pleasurable impressions and also painful

experiences; he must move with dignity through both. He must never be

unmanned nor disconcerted. This does not produce lack of feeling, but it

brings man to the steady centre within the ebbing and flowing tide of

life around him. He has himself always in hand." [5]

Here we can see how our soul life has a great effect on our physical

organism. Among many impacts, feelings have also an important role by

the fact that "health consists in the inner balance in

the human being between forces of sympathy which lead to inflammation

and forces of antipathy which lead to sclerosis. Thus health is

essentially a problem of soul balance." [6] Of course, this does not

refer to short lived feelings which can change like weather, but to the

deep-seated emotional attitudes towards life and to their subtle

physiological effects. [7] We can get an idea of this influence if we

know that "the nerve system is the expression of the astral body. Here

the astral body is the motivator, the constructor. We can imagine that

just as the clock or a machine are constructed by a watchmaker or

mechanic, thus the nerves are also constructed by the astral body." [8]

The astral or the soul-body "is the bearer of feeling, of happiness and

suffering, joy and pain, emotions and passions; wishes and desires, too,

are anchored in the astral body." [9]

If this fact is linked to the task of the nervous system in the partial maintenance of homeostatic balance, we

can start to understand the influence of soul life on the state of the

whole organism. Of course, this does not mean that health is dependent

only on our soul balance, for this would be contrary to the holistic

approach. The right approach demands that in the case of any internal

disease we need to take into account also the person's soul life,

especially those deeper one-sided moods of the soul which have

contributed to the development of a specific illness.

Spiritual Balance: Development of Virtues on the Basis of Knowledge

What is the challenge with balancing on the spiritual level?

Here we enter into the realm of moral values. Human beings have the ability

of self-conscious examination of their own behaviour. This enables us to

learn from the past experiences and thus change our behaviour. In this way

we can develop new virtues which we did not posses before and thus avoid

unhealthy extremes. In this process we need to find the balance between two

polar tendencies. In the past "the pupils of the

Mysteries were shown

that human nature can bring about destruction and harm in two directions,

and that human beings are in a position to develop free will only because of

this possibility of erring in two directions. Life can take a favourable

course only when these two lines of deviation are considered to be like the

two sides of a balance: as one side goes up the other side goes down, and

true balance is achieved only when the crossbeam is horizontal. On this

account, at the head of the moral code in all the Mysteries stood the

important dictum: You must find the mean, so that through your deeds you do

not lose yourself to the world, nor let the world lose you. That is why

Aristotle gives this curious definition of virtue: Virtue is human capacity

or skill guided by reason and insight, which in relation to the human being

holds the mean between the too-much and the too-little." [10]

Let's take one example, the attribute of courage. It can swing

between two extremes: too little is cowardice; too much is reckless

courage which doesn't give heed to dangers, so the person can easily

harm himself or even lose his life. In the first case we are not of much

use to the world, because we are not capable of doing what is needed. In

the second case we are stopped from accomplishing the needed changes

because of injury, which could be prevented if we were able to find the

golden mean and thus develop the virtue of courage. Thus we are lost to

the world in the case of cowardice, and lost in the world in the case of

recklessness.

Another example is the attribute which expresses itself in our

relationship to other people, in empathy. If this attribute develops

only in one direction, it can become an excessive worry for others; the

other extreme is indifference. The occurrence of indifference is an

example when a person hardens inwardly in his own egoism and therefore

he cannot benefit the rest of the world. However, excessive care for

others is also an expression of an unhealthy relationship to people, for

in such a case a person easily forgets about his own basic needs because

he is so given up to others. If this attitude is of long standing it

will lead to illness or complete exhaustion of one's own power – that

is, to losing oneself in the world. Thus empathy becomes virtue only if

there is not too little or too much of it.

Now, let's take an example of forming judgements about beings,

things, and phenomena we encounter. For a healthy attitude "it is important to develop the quality of 'impartiality'.

Every human being has had his own experiences and has formed from them a

fixed set of opinions according to which he directs his life. Just as

conformity to experience is of course necessary, on the one hand, it is

also important that he who would (like to) pass to higher knowledge should

always keep an eye open for everything new and unfamiliar that confronts

him. He will be as cautious as possible with judgements such as "That

is impossible!" or "That cannot be!" We have most decidedly to base our

judgement of what confronts us now upon past experience. That is one

side of the balance, but on the other there is the need to be ready

all the time for entirely new experiences – above all, to admit (to

ourselves) the possibility that the new may contradict the old," [11]

the already existing. In this manner we establish balance between

former experiences and insights that tends to ossify, and between

complete openness towards everything new which enter through our

perceptions and ideas. Thus we are developing a spiritual virtue of

forming right judgement which is one of the basic conditions for true

cognition of the world that surrounds us.