Three Different States of Our Inner Soul Life

“When we reflect upon the nature of the life of soul even with more or less

superficial self-knowledge, we realise that sense-impressions and the

thoughts

we form about them are the only clear and definite experiences in the life of

soul in which, with ordinary consciousness, we are completely awake. As well as

these thoughts and sense-impressions, sense-perceptions, we also have, of course,

the life of feeling. But just think how vaguely our feelings surge

through us, how little we can speak of inner, wide-awake clarity in connection

with our life of feeling. Anyone who faces these facts with an open mind will

certainly admit that as compared with thoughts,

our feelings are vague,

lacking in definition.

True, the life of feeling concerns us in a more intimate, personal

way than does the life of thought, but for all that there is something

undefined in it and also in the way it functions. We shall not so

readily allow our thoughts to deviate from those of other people when it

is a question of reflecting about something that is supposed to be true.

We shall feel that our thoughts and our sense-impressions must somehow

correspond with those of others.

With

our feelings it is different. We allow ourselves the right to feel in a more

intimate, more personal way. And if we compare feelings with dreams, we shall

say: dreams arise from the night-life, feelings from the depths of soul into the

light of day-consciousness. But again, in respect of their pictures,

feelings

are as indeterminate as dreams. Anyone who makes the comparison, even with such

dreams as enter quite distinctly into his consciousness, will realise that their

lack of definition is just as great as that of feelings.

Therefore we can say:

it is only in our sense-impressions and thoughts that we are really awake; in

our feelings we dream – even during waking life. In ordinary waking life, too,

our feelings make us into dreamers.

And still more so the Will! [1] When we say:

‘Now I am going to do this, or that’ – how much of

the subsequent process is actually in our consciousness? Suppose I want

to take hold of something. The mental picture comes first, then this

picture completely fades away and in my ordinary consciousness I know

nothing of how the impulse contained in the ‘I want’ finds its way into

my nerves, into my muscles, into my bones. When I conceive the idea, ‘I

want to get hold of the clock’, does my ordinary consciousness know

anything at all of how this impulse penetrates into my arm which then

reaches out for the clock? It is only through another sense-impression,

another mental picture, that I perceive what has actually happened. With

my ordinary consciousness I sleep through what has happened

in-between, just as in the night I sleep through and am unaware of

what is happening to my whole being. I am as unconscious of the one as of the other.

In waking life, therefore, there are three different and distinct states of

consciousness. In the activity of thinking we are

awake, completely

awake; in the activity of feeling we dream; in the activity of willing

we are asleep. We are in a state of perpetual sleep as far as the

essential core of the Will is concerned, for it lies deep, deep down in

the region of the subconscious.” [2]

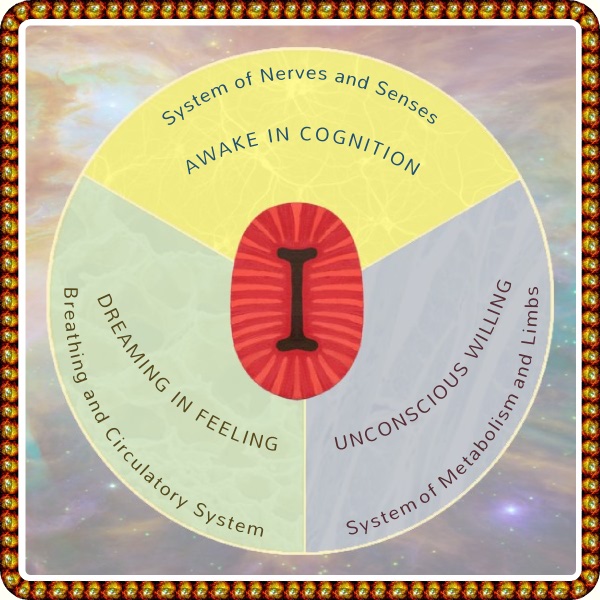

If we now relate this to the

THREEFOLD HUMAN BEING, we can summarize

our inner soul life in following manner:

- The system of nerves and senses provides the bodily

foundations for the waking life of cognition which includes

perceiving and thinking.

- The rhythmic system (the breathing system and the system of blood

circulation) provides the bodily foundations for the

dreaming life of feelings – that is, inner sensations of comfort

or discomfort with the state of our being, and of sympathies or antipathies

towards that which is continually entering us from the outside world.

- The system of metabolism and limbs provides the bodily foundations for the

sleeping life of Will which is active below our

level of ordinary consciousness.

This distinction of various states of human consciousness is an essential

part of any attempt to understand the problems of nutrition from a holistic

perspective, for in nutrition we are dealing to a large extent with the

processes of digestion and metabolism which are happening inside our organism

below the threshold of

our consciousness.

Cognition, Feeling and Willing from the Spiritual Perspective

“If you want to examine the human being effectively from any point of

view you must return again and again to the separation of man’s soul

activities into cognition which takes place in thought and into feeling

and willing. From the spiritual point of view you will find a difference

between willing, feeling and thinking-knowing.

When you have knowledge through thought you must feel that in a

certain way you are living in the light. You cognise, and you feel

yourself with your ego right in the midst of this activity of

cognition.

It is as though every part, every bit of the activity which we call

cognition, were there within all that your ego does; and again what your

ego does is there within the activity of cognition. You are entirely in

the light; you live in a fully conscious activity. And it would be bad

indeed if you were not in a fully conscious activity in cognising.

Suppose for a moment that you had the feeling that while you were

forming a judgment something happened to your ego somewhere in the

subconscious and that your judgment was the result of this process.

For instance you say: ‘That man is a good man’, thus forming a

judgment. You must be conscious that what you need in order to form this

judgment – the subject ‘man’ and the

predicate ‘is good’ – are parts of

a process which is clearly before you and which is permeated by the

light of consciousness. If you had to assume that some demon or some

mechanism of nature had tied up the ‘man’ with the ‘being good’ while

you were forming the judgment, then you would not be fully, consciously

present in this act of thought, of cognition: in some part of the

judgment you would be unconscious. That is the essential thing about

thinking cognition, that you are present in complete consciousness in

the whole foundation of its activity.

That is not the case in willing. You know that when you perform the

simplest kind of willing, for instance walking, you are only really

fully conscious in your mental picture of the walking. You know nothing

of what takes place in your muscles whilst one leg moves forward after

the other; nothing of what takes place in the mechanism and organism of

your body. Just think of what you would have to learn of the world if

you had to perform consciously all the arrangements involved when you

want to walk. You would have to know exactly how much of the activity

produced by your food in the muscles of your legs and other parts of

your body is used up in the effort of walking. You have never reckoned

out how much you use up of what your food brings to you. You know quite

well that all this happens unconsciously in your bodily nature. When we

Will there is always something deeply, unconsciously present in the

activity.” [3]

And our life of “feeling stands midway between willing and thinking-cognition.

Feeling is partly permeated by consciousness and partly by an

unconscious element. In this way feeling on the one hand shares the

character of cognition-thinking, and on the other hand the character of

feeling or felt will. What is this then really from a spiritual point of

view?

You will only arrive at a true answer to this question if you can

grasp the facts characterised above in the following way. In our

ordinary life we speak of being awake, of the waking condition of

consciousness. But we only have this waking condition of consciousness

in the activity of our knowing-thinking. If therefore you want to say

absolutely correctly how far a human being is awake you will be obliged

to say: A human being is really only awake as long and in so far as he

thinks of or knows something.

What then is the position with regard to the Will? You all know the

sleep condition of consciousness – you can also call it, if you like,

the condition of unconsciousness – you know that what we experience

while we sleep, from falling asleep until we wake, is not in our

consciousness. Now it is just the same with all that passes through our

Will as an unconscious element. In so far as we as human beings are

beings of Will, we are ‘asleep’ even when we are awake. We are always

carrying about with us a sleeping human being – that is, the willing man

– and he is accompanied by the waking man, by the man of cognition and

thought. In so far as we are beings of Will we are asleep even from the

time we wake up until we fall asleep. There is always something asleep

in us, namely: the inner being of Will. We are no more conscious of that

than we are of the processes which go on during sleep. We do not

understand the human being completely unless we know that sleep plays

into his waking life, in so far as he is a being of Will.

Feeling stands between thinking and willing, and we may now ask: How

is it with regard to consciousness in feeling? That too is midway

between waking and sleeping. You know the feelings in your soul just as

you know your dreams – with the only difference that you remember your

dreams and have a direct experience of your feelings. But the inner mood

and condition of soul which you have with regard to your feelings is

just the same as you have with regard to your dreams. Whilst you are

awake you are not only a waking man in that you think and know, and a

sleeping man in that you Will: you are also a ‘dreamer’ in that you

feel. Thus we are really immersed in three conditions of consciousness

during our waking life:

- the waking condition in its real sense

in thinking and knowing

- the dreaming condition in

feeling

- and the sleeping condition in

willing.

Seen from the spiritual point of view ordinary dreamless sleep is a condition

in which a man gives himself up in his whole soul being to that to which he is

given up in his willing nature during his daily life. The only difference is

that in real sleep we ‘sleep’ with the whole soul being, and when we are awake

we only sleep with our Will. In dreaming as it is called in ordinary life we are

given up with our whole being to the condition of soul which we call the ‘dream’

and in waking life we only give ourselves up in our feeling nature to this

dreaming soul condition.” [4]